Researching Dissent & Discipline

Topics: Vietnam War; Black Panthers; South African apartheid; Audobon Ballroom; Barnard Judicial Council; Student discipline; Censure; Suspension; Expulsion

Anti-War and Civil Rights Protests

The student uprisings at Columbia University during the late 1960s and early 1970s are well documented in Barnard and Columbia archival collections, and have previously been explored in published works such as this 2018 Barnard Magazine article, and digital exhibitions such as 1968: Columbia in Crisis and From LeClair to Low Library: Barnard’s Spring of 1968. The demonstrations that took place on both Columbia and Barnard campuses during these years were launched by students protesting a range of interconnected issues, namely the Columbia administation’s support for the United States’ military intervention in Vietnam, anti-Black racist violence and discrimination, and Columbia’s efforts to build a gymanasium in Morningside Park that would exclude members of the surrounding Harlem neihborhood. The materials presented in this section shed light on Barnard students’ involvement in and support for these protests, as well as the responses from Barnard alums, administration, and parents. The materials featured in this section are sourced from the President’s Office Records and Office of Communications Records

On May 7, 1965, Barnard and Columbia students gathered at Ferris Booth Hall and Low Library during an annual awards ceremony for the NROTC (Naval Reserve Officers Training Corps) at Columbia, a program that trains college students to become officers in the US Navy and Marine Corps. This letter from Zane Berzins (BC ‘65) provides Berzins’s account of the violent police response to the protest:

Berzins was one of several Barnard students who wrote to Dean Henry Boorse, Barnard’s Dean of the Faculty, describing the nature of the protest and their participation in it to protest the police’s violence toward students and the administration’s disciplinary actions taken against a few students. Some students signed boilerplate statements confirming their participation or support for the protest, and voicing their opposition to the administration’s actions to discipline protestors.

In this letter, Jemera Rone Flug (BC ‘66) criticizes what she calls the administration’s “complete lack of respect for due process” in the disciplinary hearings against student protestors:

However, Barnard President Martha Peterson responded to many of these testimonies, including the letter from Zane Berzins, with further disciplinary action:

The Judicial Council mentioned by President Peterson was created just one year prior in 1964. According to the 1965-66 Barnard Student Handbook, the Council comprised of 5-7 students who were elected by the student body and 2-4 faculty members elected by the faculty. The Dean of Studies and President of the College were ex officio members. However, there was no official student code of conduct at Barnard until 1971. Thus, the grounds on which the Judicial Council prosecuted students for non-academic offenses are murky.

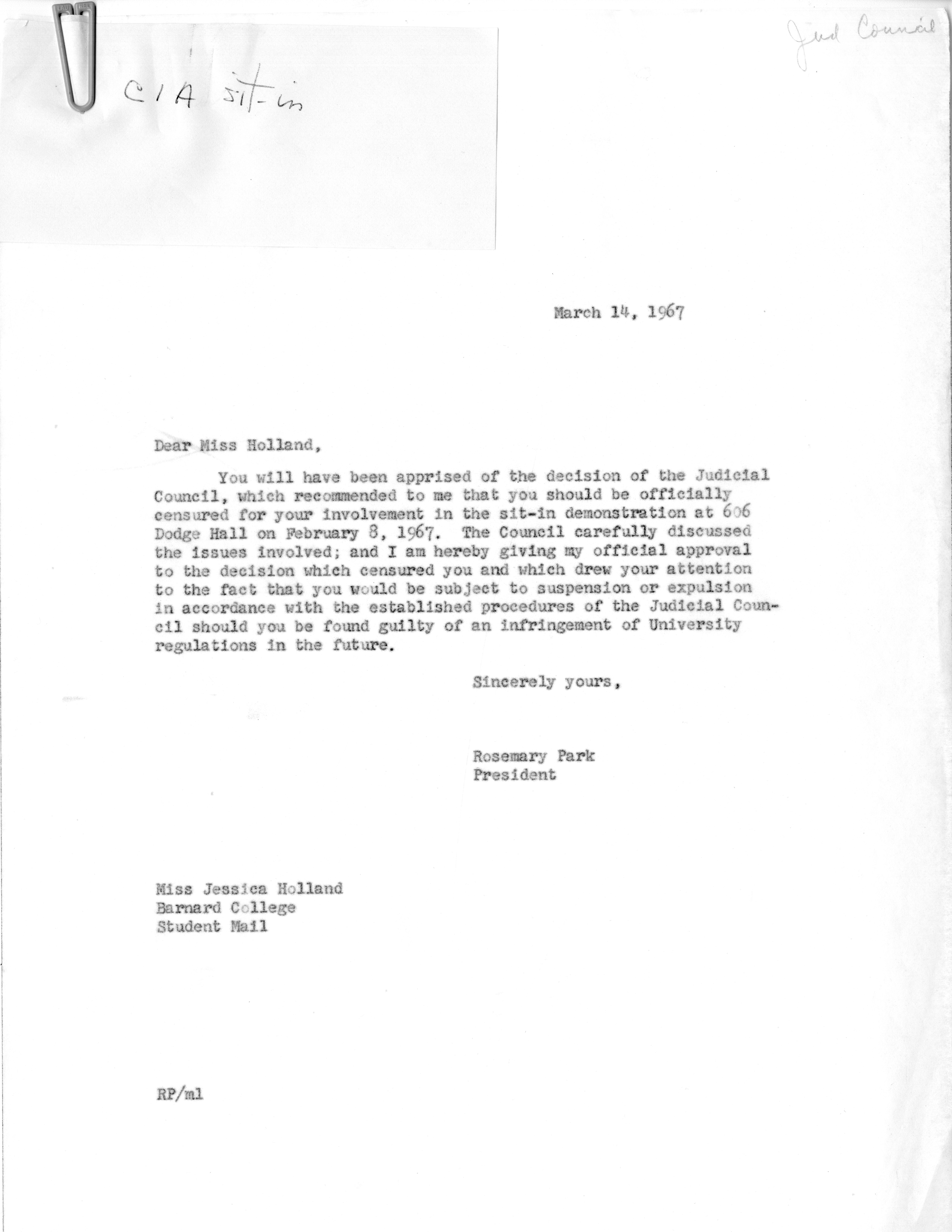

The disciplinary procedures that the Judicial Council undertook in response to anti-war protests are illuminated in these letters from Margaret Emery, Chairman of the Judicial Council, to Jessica Holland regarding her protest activities in January and February of 1967:

Barnard President Rosemary Park confirmed the official censure of Holland in this letter:

In the following letter from the Judicial Council, they issued what appears to be a warning to Suzanne Crowell for her participation in a protest of an NROTC course:

Starting in April 1968, student members and supporters of Columbia’s Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) chapter and the Society of Afro-American Students (SAS) launched several major demonstrations and occupations protesting the universities’ involvement in the Vietnam War and construction of the Morningside Park gymnasium. Beginning with a dual SDS and SAS rally at Columbia’s Sun Dial at noon on Tuesday, April 23, demonstrations evolved into several days-long occupations campus buildings by Barnard and Columbia students, as well as non-Columbia affiliated protestors. Hamilton Hall, Fayerweather Hall, Low Library, Avery Hall, and the Mathematics Hall, all on Columbia’s campus, were occupied. Estimates of Barnard students’ participation in the protests range from 100 to 300. Several Black Barnard students who participated in the occupations went on to become members of the Barnard Organization of Soul Sisters (BOSS), which was formed later in 1968 and whose records are preserved in the Barnard Organization of Soul and Solidarity (B.O.S.S.) collection, BC37-02.

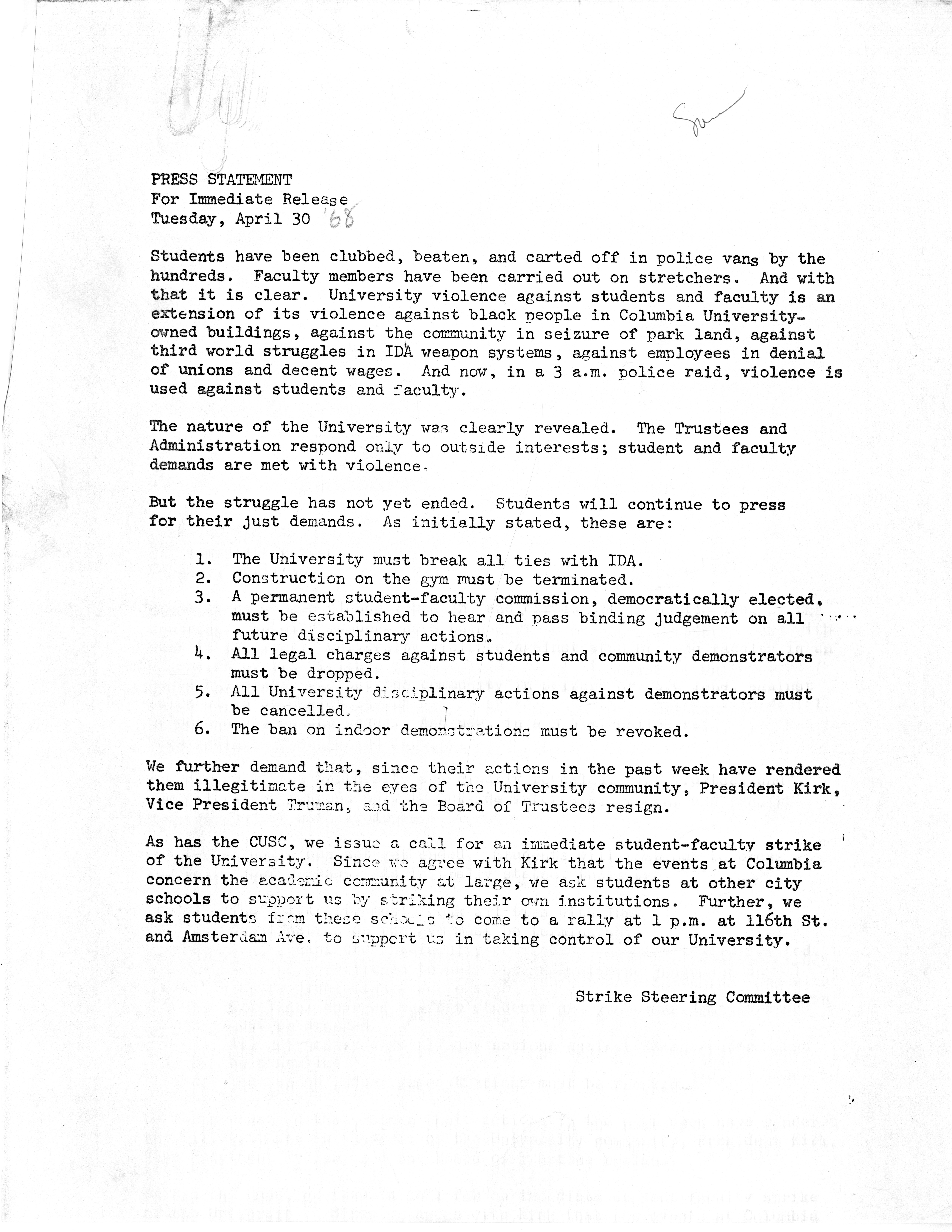

The occupations were brought to a violent end on Tuesday, April 30, 1968 when New York City police fordibly removed student protestors, resulting in over 700 arrests of student protestors, including 111 Barnard students, and at least 148 injuries. The digital exhibition 1968: Columbia in Crisis presents a detailed timeline of events with supporting archival materials from the Columbia University Archives and private collections.

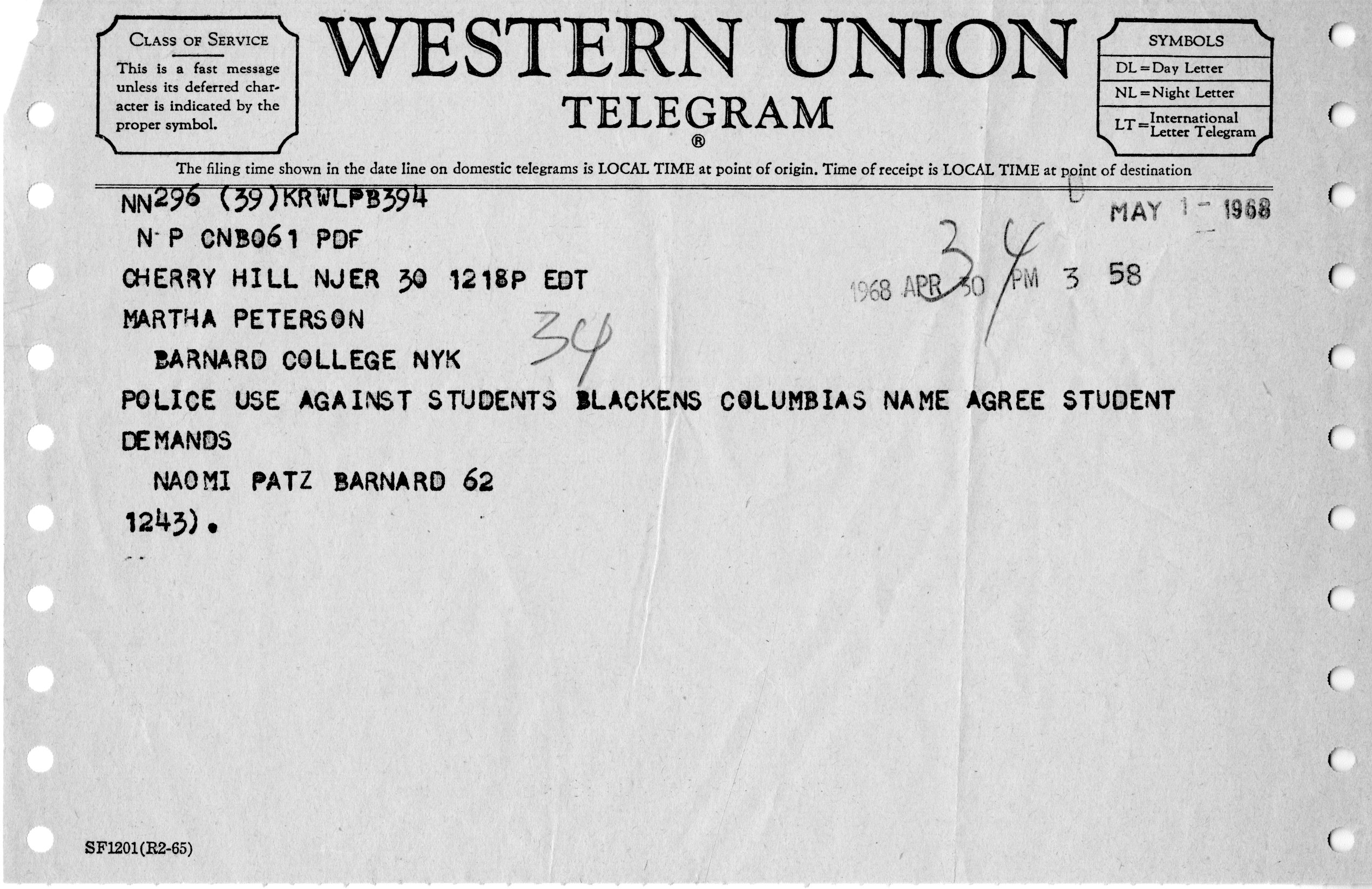

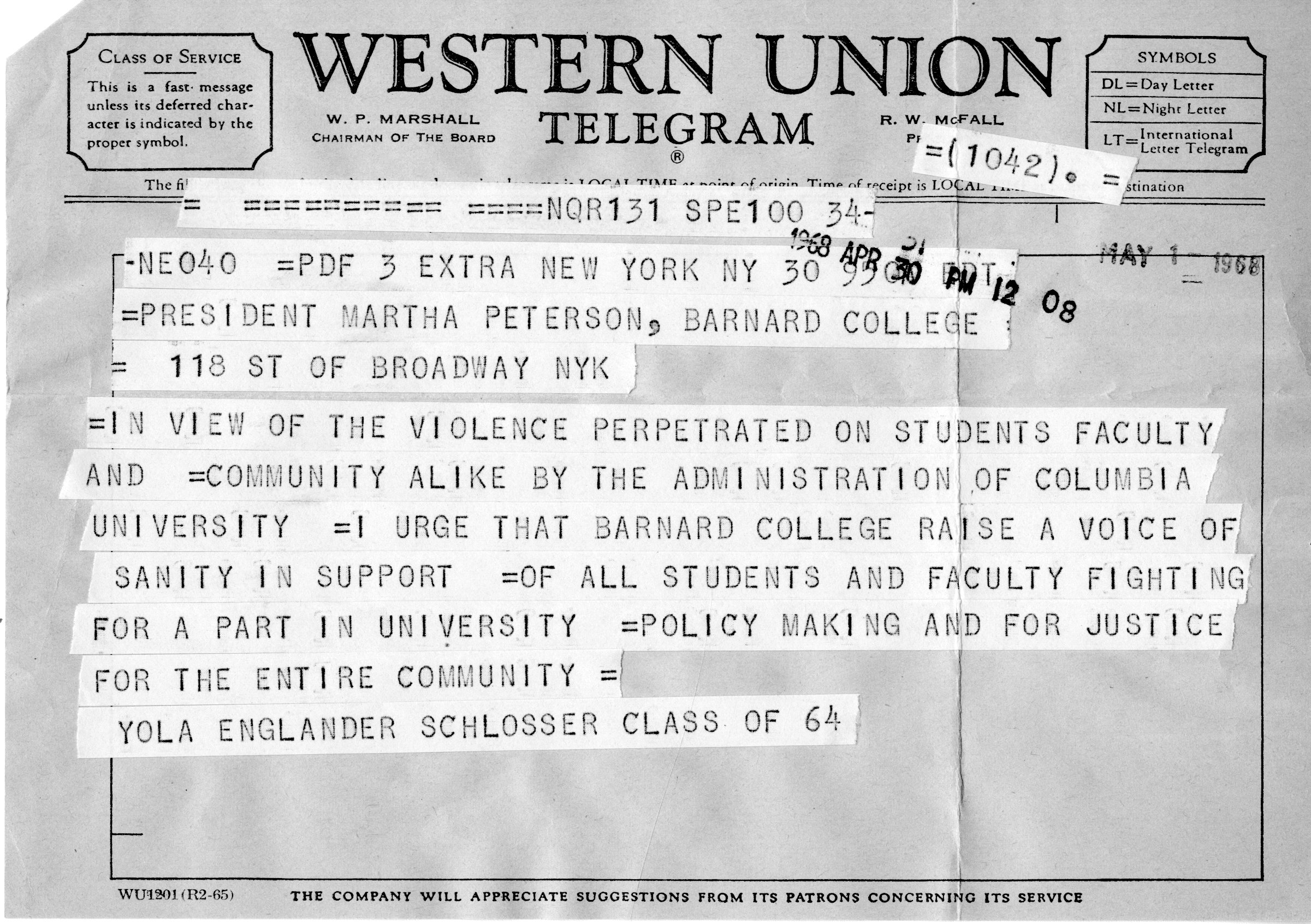

Two telegrams from Barnard alums sent immediately after the police raid demonstrate their alarm and disapproval of the use of police force:

The events of April 30 also prompted the following statements from the student members of the Executive Board of the Undergraduate Association and members of the Voting Faculty, Teaching Staff, and Administration:

In the aftermath of the April 30 “bust,” several students who participated in the strike formed the Strike Coordinating Committee to organize a campus-wide strike at Columbia for the rest of the spring 1968 semester. Strikers encouraged students and faculty to refrain from attending classes, and also called for Columbia President Kirk, Vice President Truman, and the Board of Trustees to resign.

On May 21, 1968, over a hundred SDS members occupied Hamilton Hall once again, which led to another violent police response in the early hours of May 22.

This document presents a list of Barnard students who were arrested at this time:

Columbia President Grayson Kirk and Vice President David Truman released statements strongly condemning the student protestors and promising disciplinary action:

It is unclear whether there was a press statement from Barnard President Martha Peterson released to the public, however in this letter, Peterson expresses her hesitation to release such a statement:

Parents of Barnard and Columbia students were also compelled to voice their opinions on the 1968 riots. Parents’ reactions ranged from condemnation of the student protestors and support for the administration’s actions, to supportive sentiments for the students and disapproval of the administration.

The President’s Office records contain materials that reflects Barnard’s and Columbia’s participation in the worldwide Moratorium to End the War in Vietnam on October 15, 1969.

This memo from the Barnard Moratorium Committee lists an itinerary of events to be held on Barnard’s campus on Moratorium day:

This letter, which is potentially an unsent draft due to its lack of signatures, was prepared by an unknown group of Barnard community members on Moratorium day to be sent to the President of the United States, Richard Nixon. The letter decries the escalation of the Vietnam War as well as the villanization of anti-war advocates and censure of anti-war speech:

Amidst anti-war protests, members of SDS, SAS, and BOSS also organized campus and regional actions to protest the brutalization, arrests, and murders of Black Panther actvists:

In 1969, BOSS issued a list of ten demands to Barnard administration including demands for equitable housing, a dedicated campus space, courses and library materials on African American studies, and increased recruitment of Black students, among other demands. President Martha Peterson offered a response to the demands at a convocation of students on March 3, however President Peterson’s response was not satisfactory to BOSS and was rejected by the group entirely. The spring 1969 issue of Barnard Alumnae, Barnard’s alum magazine, offered an account of the events leading up to the conflict and printed the statements made by both BOSS and President Peterson.

In 2019, BOSS E-Board members Maat Bates and Denise Mantey created an exhibit honoring BOSS’ 50th anniversary and looking back on the demands that BOSS made of Barnard’s administration in 1969. The multi-faceted and interactive exhibit was displayed in the Altschul lounge and later brought to the Archives Reading Room. In the exhibit, Bates and Mantey offered perspectives on BOSS’s past, present, and future; reflected on the impact of the 1969 demands on the lives of Black students and Barnard; and named the ways in which demands presented in 1969 have still not yet been addressed by the College. Materials featured in the exhibit are preserved in the Barnard Organization of Soul and Solidarity (B.O.S.S.) collection, BC37-02

While not focused specifically on BOSS, Black @ Barnard: Analyzing How Black Barnard Students Exist On Campus is another exhibition that charts the historical legacies of Black students at Barnard. Curated by Corinth Jackson ‘20, Black @ Barnard is available to view online.

The President’s Office records also contain materials related to protest and strike activities in the spring of 1972, launched in response to the escalation of the Vietnam War. Several documents relate to a mass strike meeeting held at McIntosh Center on Barnard’s campus on April 18, 1972, as well as strike and protest activities that followed.

Strike and protest activities escalated, leading to the occupation of five Columbia buildings by both pro-strike and anti-strike student and faculty protestors from April 25 through May 12. This statement from the Columbia Office of Public Information summarizes university disciplinary actions and criminal charges brought against student protestors:

South African Apartheid

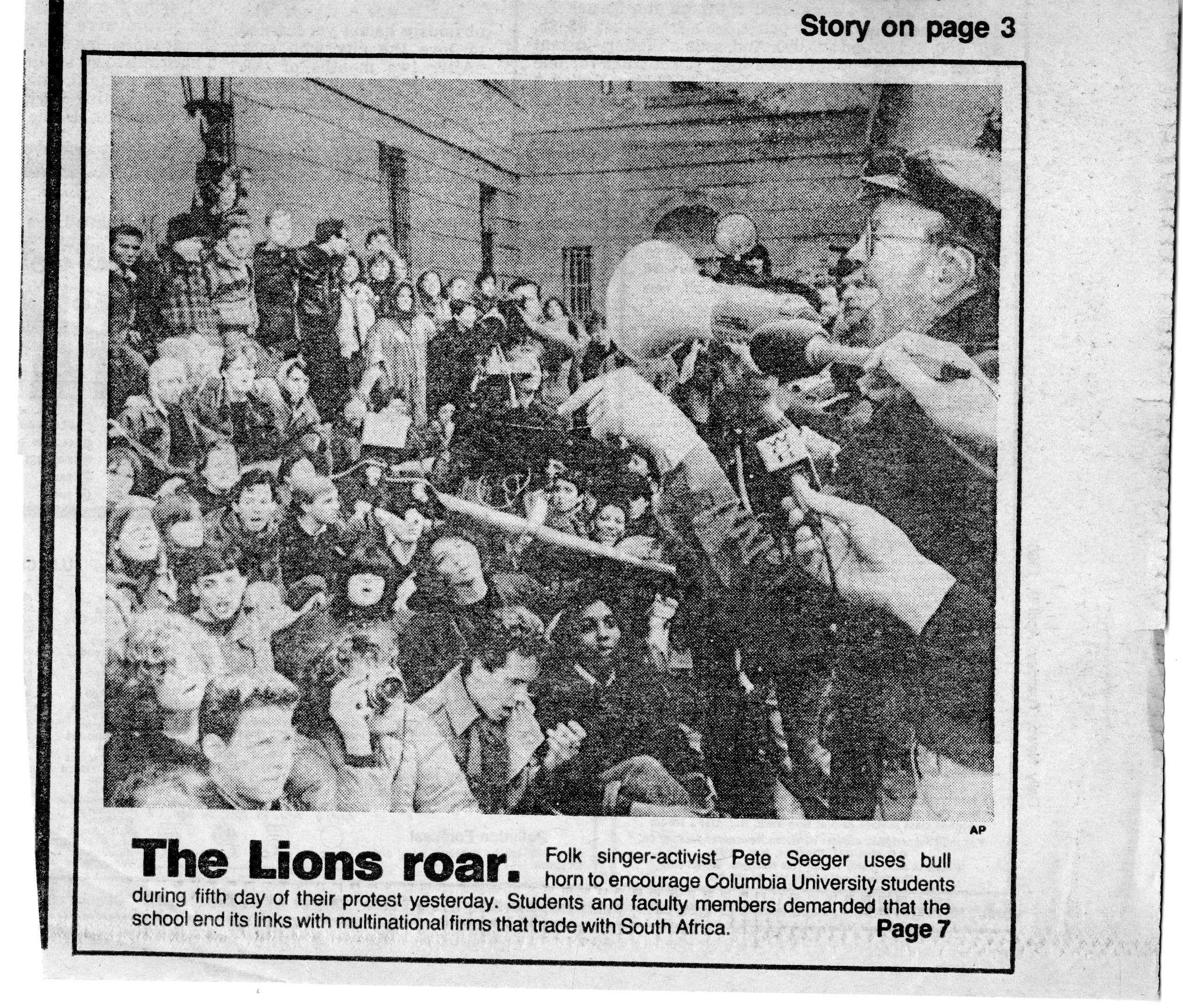

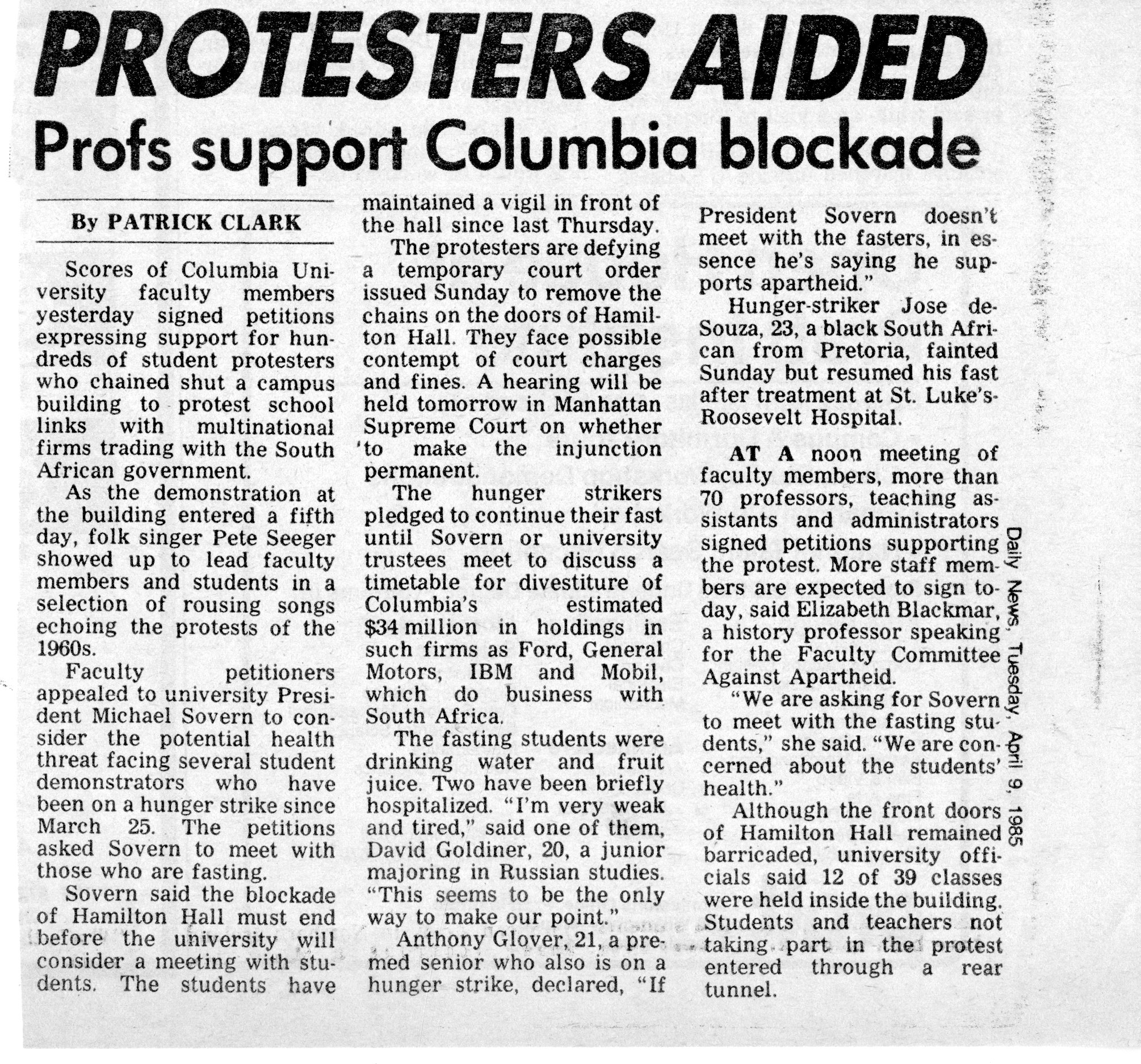

Beginning on April 4, 1985, student protestors blockaded and occupied Hamilton Hall to protest racial apartheid in South Africa and demand that Columbia divest from businesses operating there. The occupation began following a rally organized by the Coalition for a Free South Africa in conjunction with a national day of divestment protests. Additionally, by the time occupation of Hamilton Hall began, several students and faculty had already been on hunger strike since March 25.

Six days into the occupation, Barnard students received the following statement from Barbara Schmitter, Vice President and Dean of Student Affairs (later renamed to Dean of the College), warning students of disciplinary actions that would be taken against students participating in any occupation or blockade of university buildings:

On or around the same day, Barnard members of the Coalition for a Free South Africa released their own statement demanding divestment and criticizing the administration’s disciplinary procedures and targeting of a small number of student protestors:

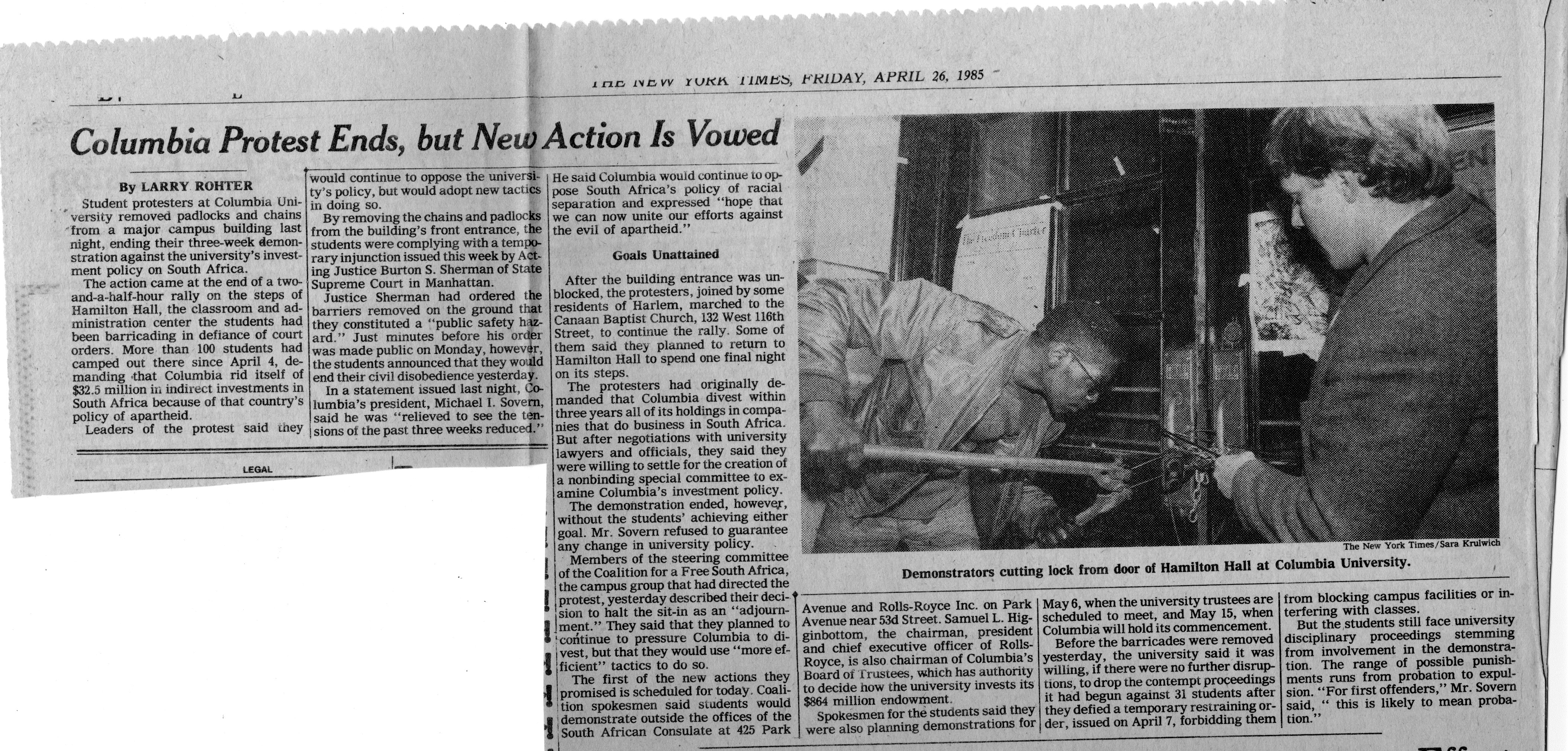

After three weeks, the blockade came to an end on April 25, 1985.

See the Divestment section of this workshop plan to view the resolutions of Columbia and Barnard Trustees to divest from businesses operating in South Africa in the months following the protests.

Audobon Ballroom

On December 14, 1992, approximately 100 students blockaded Hamilton Hall for several hours in protest of the Columbia administration’s plans to build a biomedical research center on the site of the Audobon Ballroom, the historic Washington Heights venue where Malcolm X was assassinated on February 21, 1965.

Barnard students who were involved in the protest were contacted by Barbara Schmitter:

Questions & Group Exercise

- What is the document? Who created the document, when did they create it, where did they created, why did they create it, and how did they create it?

- Where does your eye go first? What do you see that you didn’t expect?

- Are there any additional actors or voices aside from the creator(s) who left their mark on the material? What marks have archivists left? What do these marks tell you about the intentios behind the collection and preservation of the material?

- What is not communicated in the document and why?

- What can you infer about the broader campus, city, national, and/or international context in which a particular material was created?

- How would you contextualize this item within a larger research project or question? What other types of sources would you need to answer your questions about this item?

- What role do optics and performance play in expressing dissent? What role do optics and performance play in demanding or enforcing disciplinary measures? How are those aspects captured in these materials, or not?

- Archivists are responsible for protecting the privacy and legal rights of people who are captured in the archive. This includes those who created the materials as well as those who are mentioned within the materials.

- What is at risk for those who are featured in archival materials?

- How might risks be different depending on one’s status as a student, faculty member, staff member, or administrator?

- Today, campus communities receive information about major policy changes, including disciplinary procedures, via email and websites.

- What feels different about encountering the administrative voice in the archive versus encountering it on the internet or in the media?

- In what ways are digital records more vulnerable than physical files? Vice versa?

Find examples of disciplinary policies posted on university websites and compare them to the materials presented here. Consider: What is similar about the language and tone? Is it easy to tell who created or wrote it? Do you see any evidence of revisions or omissions?

Citations

- Board of Trustees meeting minutes, 1978 - 1989, Sub-series 1.1, Box: 8. Board of Trustees Records, BC01-01. Barnard Archives and Special Collections.

- Board of Trustees meeting minutes, 1989 - 2003, Sub-series 1.1, Box: 9. Board of Trustees Records, BC01-01. Barnard Archives and Special Collections.

- Correspondence, 1970s-1980s, Sub-series 2.3, Box: 39, Folder 3. Board of Trustees Records, BC01-01. Barnard Archives and Special Collections.

- Committee on Investments, 1982 - 1990, Sub-series 3.5, Box: 63, Folders: 5-6. Board of Trustees Records, BC01-01. Barnard Archives and Special Collections.

- Committee on Investments, 1990 - 1997, Sub-series 3.5, Box: 64, Folders: 1-9. Board of Trustees Records, BC01-01. Barnard Archives and Special Collections.

- Barnard College statement on divestment from Israel, 2002-11-07, Subseries 6.1, Box: 199, Folder: 9. President's Office records, BC05-22. Barnard Archives and Special Collections.

- Divest Barnard Collection, 2010-2017; Box and Folder or URL; Barnard Archives and Special Collections, Barnard Library, Barnard College.

- Bylaws of Barnard College as of June 7, 2023, BC-01_001. Board of Trustees Records, 1882-2023; Barnard Archives and Special Collections, Barnard Library, Barnard College.

- Grady-Benson, Jessica, and Brinda Sarathy. 2016. “Fossil Fuel Divestment in US Higher Education: Student-Led Organising for Climate Justice.” Local Environment 21 (6): 661–81. doi:10.1080/13549839.2015.1009825.