This page displays some of the key findings from my analysis of EAD finding aids gathered from TARO.

Visualizations

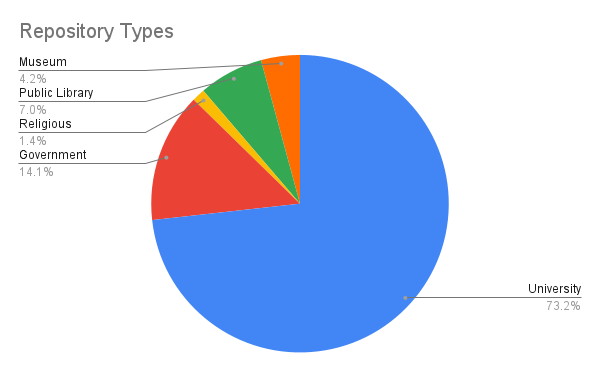

The majority of finding aids analyzed in this study were contributed by Texas universities (Figure 1). Finding aids published by the Benson Latin American Collection at the University of Texas at Austin are overrepresented in the corpus, with nearly half (30) of the finding aids under study generated from there. As a major special collections library with a subject focus on Latin America at a highly ranked research university, the Benson unsurprisingly emerges in this study as the state’s foremost repository for collections involving Black, Indigenous, and mixed-race archival subjects during the Spanish colonial period. While the Benson is the only specifically Latin American focused repository in the corpus, all of the universities represented in the study prioritize collections related to the Spanish colonial legacy in Texas, the Southwest, and Mexico.

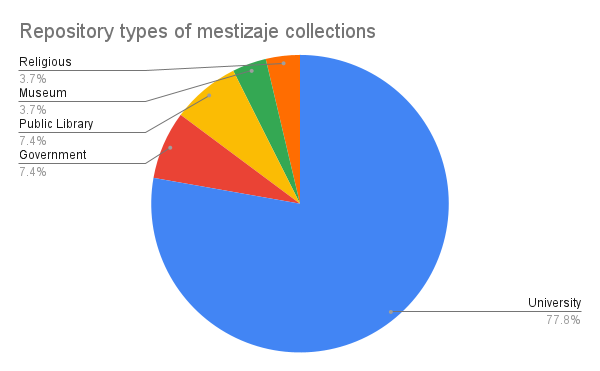

Of the 27 finding aids that include colonial-era terms for describing mixed-race people and the racial caste system, 21 were produced by universities, 2 by government archives, 1 by a museum library, 2 by public libraries, 1 by a religious institution (Figure 2). The relatively low proportion of the corpus including those descriptive terms demonstrates what was perhaps obvious at the outset of this study: mixed-race subjects are not particularly prominent in archival collections, even those related to colonial administration of the Americas. Still, within this case study, universities emerge as the clear locus of archival description of mestizaje.

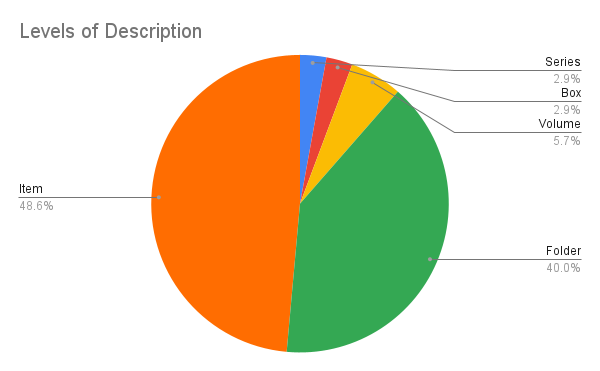

By analyzing the levels of description across the corpus, results show that the majority of finding aids have received considerable amounts of archival labor to be described at the folder and item levels (Figure 3). Based on the high amount of detailed descriptive work that has evidently been undertaken with collections in the corpus, I would assert that a lack of description, contextualization, or indexing of racial terminologies cannot simply be attested to minimal processing or lack of sufficient resources.

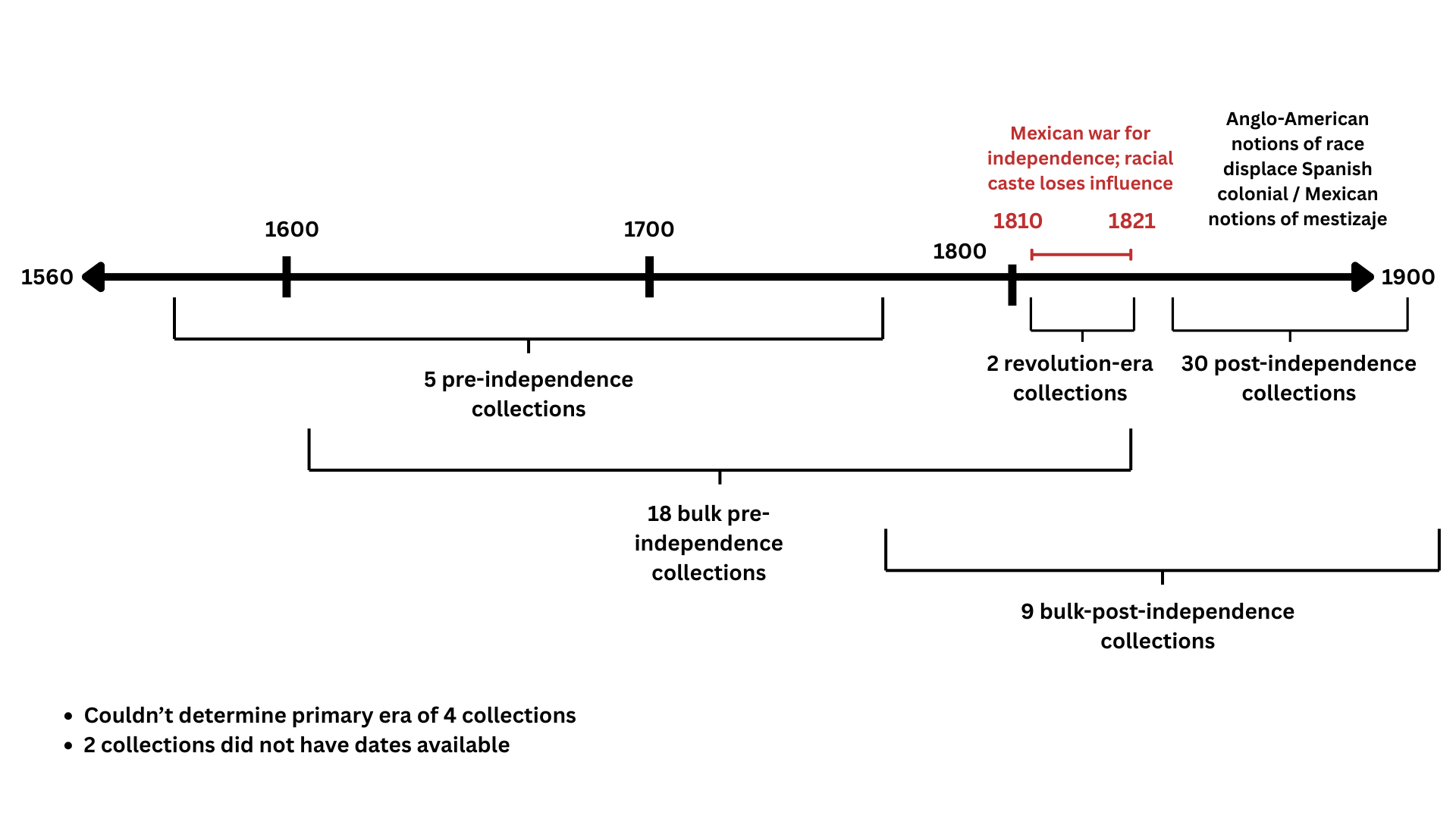

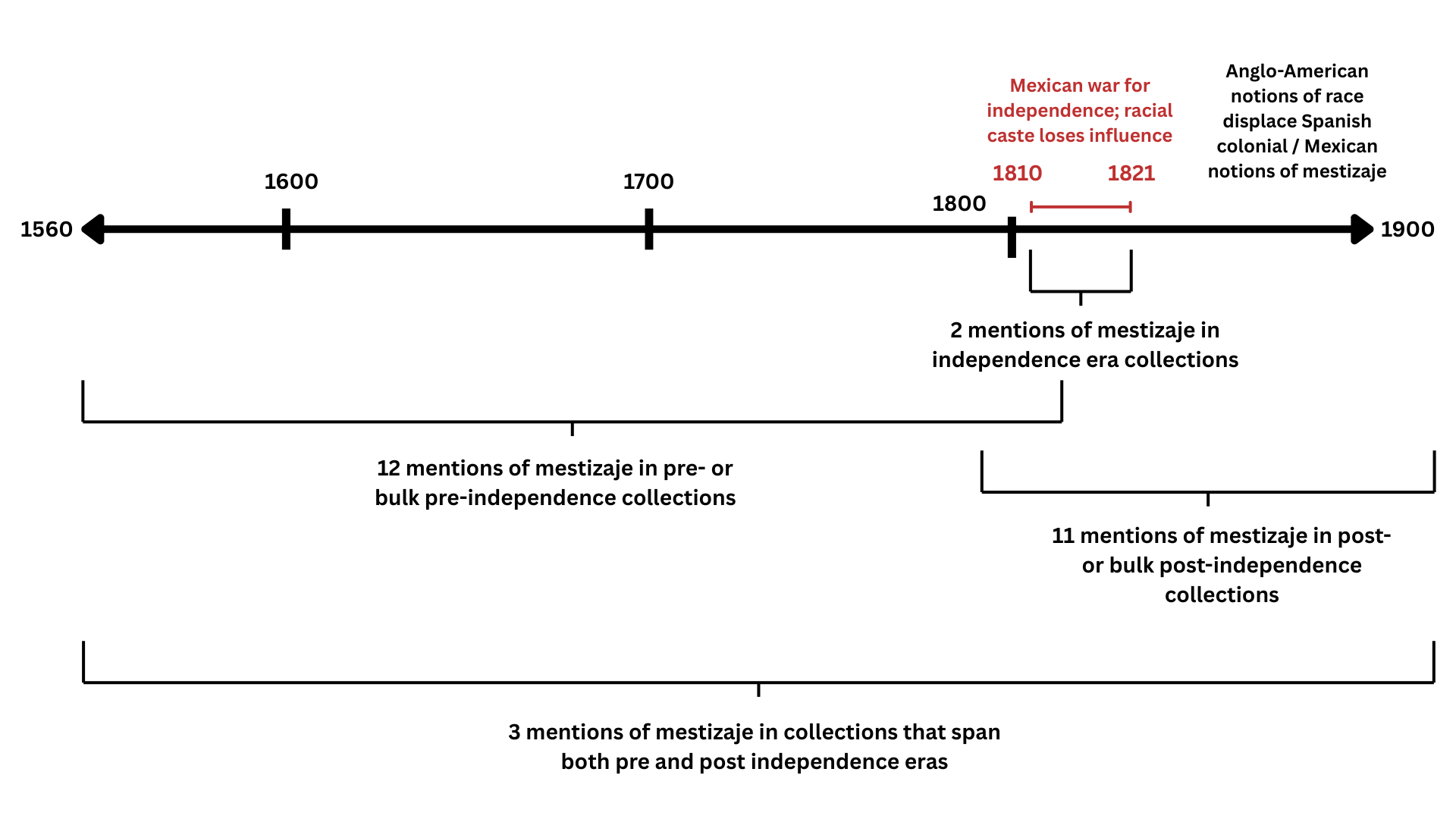

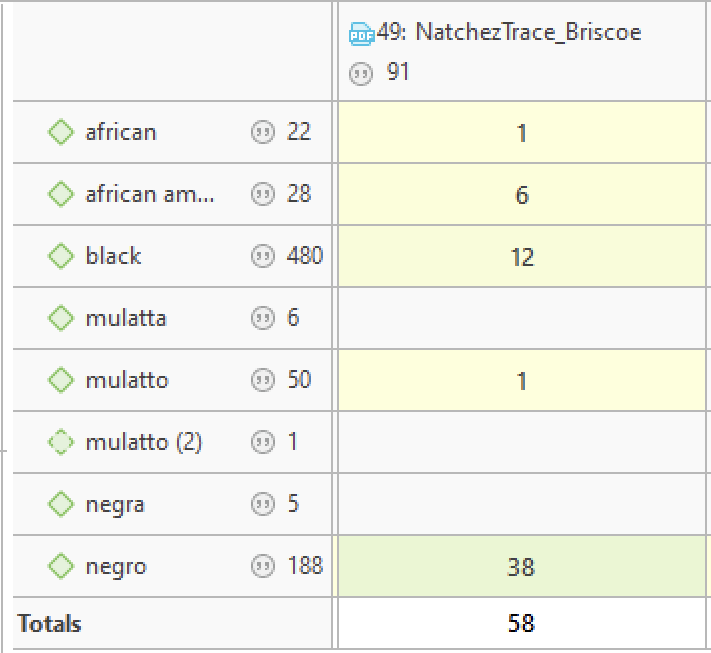

By coding the collection date extents listed in the finding aid, I found that over half of the corpus represents collections mostly or completely dated after the period of New Spain’s independence, which has been established as the effective end of racial caste terminology in hegemonic record-keeping practices (Figure 4). The overrepresentation of post-colonial collections in the corpus limits the claims I am able to make about archival descriptive practices for colonial era collections, which one would expect would have a higher volume of racial caste terminology. However, by analyzing the co-occurrences of mestizaje and caste codes with era codes, I found that there are mestizaje and caste description occurs equally in collections with date extents before and after the independence era (Figure 5). Mestizaje terms, particularly mulatto/a, were already present in Anglo-American racial imaginary and often used in documents related to the economic operation of slavery in the US. Thus, archival descriptions of mestizaje are not necessarily confined or concentrated in the archival record of the Spanish colonial era.

Key findings

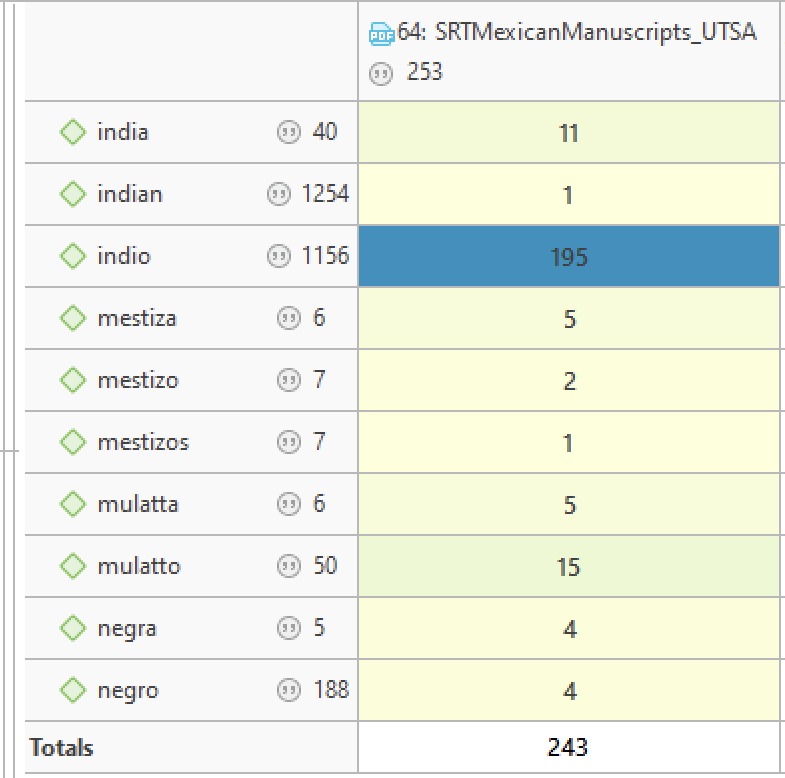

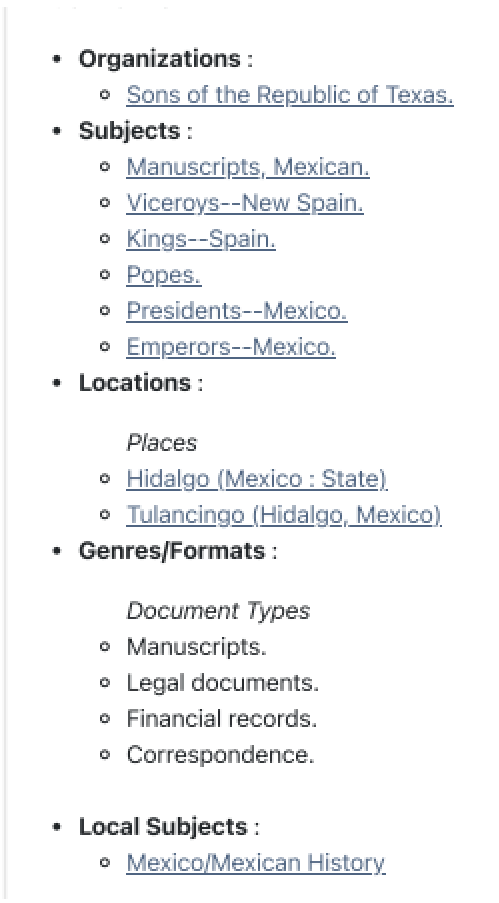

Out of 24 finding aids that included colonial terms for mestizaje in their description, none of them included subject headings that would indicate the presence of mixed-race subjects (referring to both people and topics) within the collection. Examples of LCHS headings that could have been utilized include Mestizaje, Mestizos, and Multiracial people, among others. Many of these finding aids only included 1-5 mentions of mestizo/as, which may not have warranted a subject heading at the collection level. Others, such as the Sons of the Republic of Texas Kathryn Stoner O’Connor Mexican Manuscript Collection, contain a more significant number of descriptions of racial identity yet do not include any cultural groups in the subject index (Figure 6).

Just over half (40) of the finding aids contained processing information that indicated the collection description had been created or revised since 2010. Five had last been written or revised from 2000 to 2009, 13 had been revised in 1990-1999, and 12 did not provide processing dates. Based on the increase in scholarship and activism surrounding reparative and culturally responsive description since the 2010s, I expected to find evidence of archivists applying such guidance to collections dealing directly with Black and Indigenous peoples recorded in the archive by their enslavers and colonial oppressors. However, surprisingly, only three finding aids in the corpus communicated the processing archivists’ awareness of racist materials within the collection (Figure 6) or suggested that the archivist(s) took descriptive interventions to humanize records subjects by describing people held in bondage as enslaved and including their names when available, rather than simply referring to them as slaves. While I acknowledge that this case study represents a small sample of finding aids, it is concerning to see that such a large percentage of the corpus lacked evidence of archivists’ awareness of or interventions in materials that contributed to racism, enslavement, and oppression. Such omissions, whether deliberate or not, contribute to the normalization of violence marginalization of Black and Indigenous people in the archive. The question of whether mestizaje terms are considered harmful and by whom remains an unresolved question that should be taken up by archivists and scholars of colonial Latin American in conversation with Black, Indigenous, and Latine archives users.

Only three finding aids included statements that acknowledged offensive language in collection materials