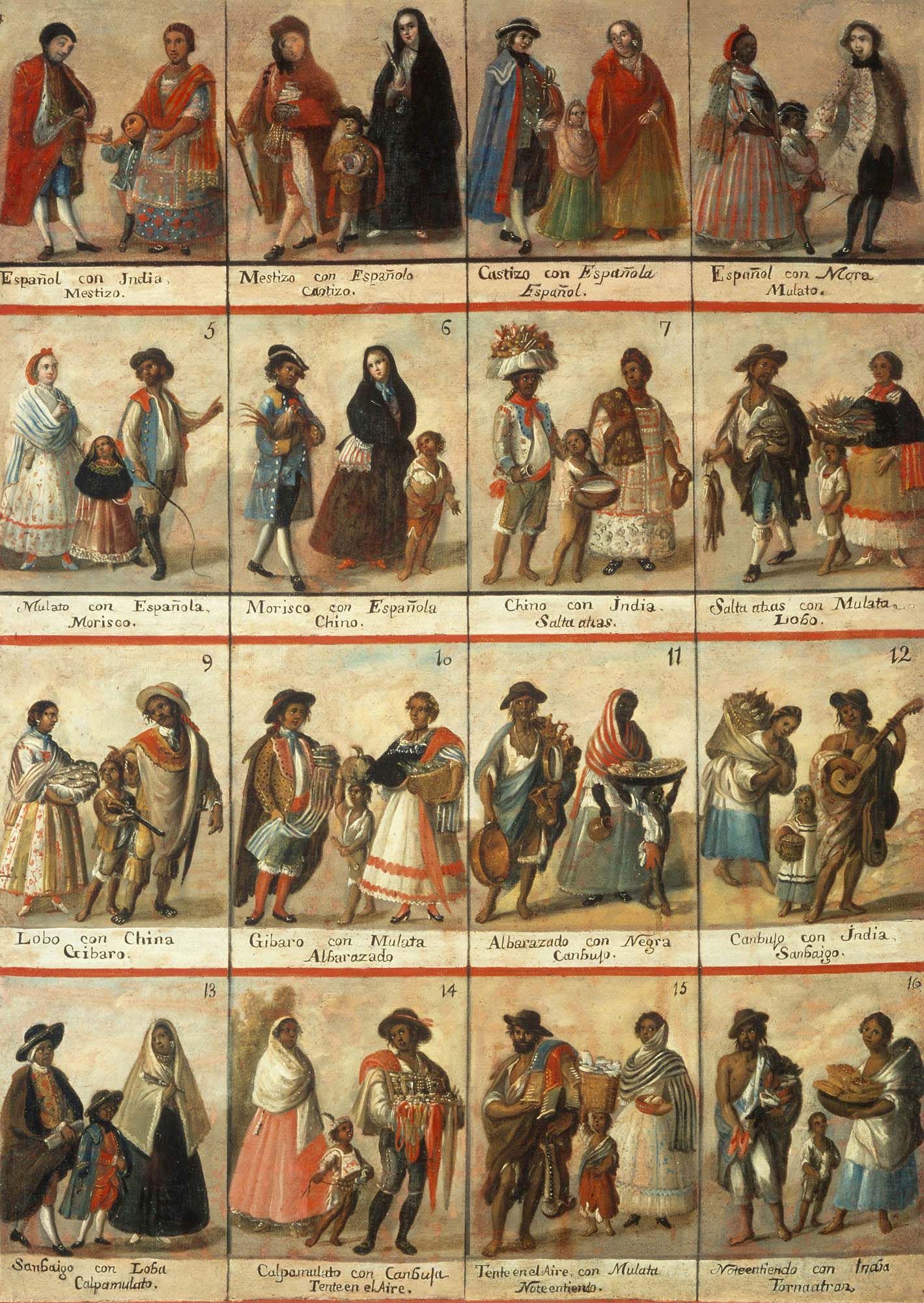

The casta painting genre, popular in the 18th century in colonial Mexico, offers a visually striking manifestation of the Spanish colonial record-keeping system and its documentation, classification, and characterization of the Black, Indigenous, and mixed-race peoples as a means of world-making and subjugation. The paintings typically depict several scenes, each with a man and a woman of different races with their mixed-race child, who is assigned a racial epithet that reflects the combination of their parents’ backgrounds. Families painted with darker skin to represent children of Indigenous and African backgrounds were usually depicted as being of lower socioeconomic station and less pleasant temperament than those with European lineage. Mestizaje refers to this concept of racial mixture.

Casta paintings are not literal representations of race and social hierarchy in Spanish colonial society, which many historians have argued were much more fluid in practice.1 For instance, Sarah Cline argues “casta paintings might well have been an attempt to fix in place rigid divisions based on race, even as they were disappearing in social reality.”2 However, the painting itself, mobilized as a tool for attempting to represent a more rigid societal order, can be seen as an instrument analogous to the colonial archive, which also used records as a vehicle for giving the impression of control over an ever-changing population. For centuries of Spanish rule, and most prominently in the Viceroyalty of New Spain (present-day Mexico and the Southwest United States), these racial labels were used to classify people in the colonial record-keeping system, from governmental court and tax documents to religious records of birth, baptism, and marriage. The most common classifications included:

- Mestizo/a: a person of mixed white European and Indigenous descent

- Mulatto/a: a person of mixed African and white European descent

- Criollo/a: White Europeans born in the New World

- Espanol/a: White Spaniards born in Europe

- Castizo/a: the child of a mestizo/a and a white European (three-quarters European)

- Indio/a: an Indigenous person of the Americas

- Negro/a: a person of African descent

- Chino/a: a person of Asian descent

Although not the caste system may not have been one of rigid social immobility, these classifications produced material consequences. For instance, between 1572 and 1810, the Spanish crown required all free people of African descent to pay a tributo, or tax, as a symbolic affirmation of their loyalty to the colonial regime. One 1793 circular, preserved at the Benson Latin American Collection at the University of Texas at Austin, reminds colonial subjects that although free Black, mestizo, and mulatto people already paid the tributo, they were also required to pay additional sales tax, or alcabalas (view the circular online here).3 In another court document dated March 24-April 11, 1557, the person accused of a crime is identified not by his name but as a “mestizo, hijo de español,” who is sentenced to 10 years of forced labor, 100 lashings, and ordered to pay two pesos of gold “por dar mal ejemplo a los indios naturales de Tulancingo.”4 One’s identification as an espanol/a or criollo/a was essential for occupying public office – with the occasional wealthy mestizo as an exception.5 Records like these from the Spanish colonial administration of the Americas are now preserved in repositories in Spain, Latin America, and the United States.

Notes

-

Giraudo, Laura (14 June 2018). “Casta(s), ‘sociedad de castas’ e indigenismo: la interpretación del pasado colonial en el siglo XX”. Nuevo Mundo Mundos Nuevos. doi:10.4000/nuevomundo.72080 ↩︎

-

Cline, Sarah. “Guadalupe and the Castas: The Power of a Singular Colonial Mexican Painting.” Mexican Studies/Estudios Mexicanos 31, no. 2 (2015): 222. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/msem.2015.31.2.218. ↩︎

-

Additional taxation for Black or mixed race free peoples of New Spain, 1793. Black Diaspora Archive Miscellaneous Manuscript Collection, Benson Latin American Collection, LLILAS Benson Latin American Studies and Collections, The University of Texas at Austin. ↩︎

-

“Cabesa de proceso contra este mestizo, hijo de español, por dar mal ejemplo a los indios naturales de Tulancingo.: Sentencia: destierro por 10 años a cumplir al servicio de Su Majestad en el muelle de la Veracruz, 100 azotes en el pueblo y 2 pesos de oro comun., 1557, marzo 24 - abril 11.” Sons of the Republic of Texas Kathryn Stoner O’Connor Mexican Manuscript Collection, MS 71, University of Texas at San Antonio Libraries Special Collections. ↩︎

-

Herrera Ángel M (2002) Ordenar para controlar. Ordenamiento especial y control político en las llanuras ↩︎